The world is watching the U.S. presidential election closely for clues on how a Kamala Harris or Donald Trump presidency will respond to mounting global challenges and security threats — and Canada could find itself in the spotlight in either scenario.

Neither Trump nor Harris have made foreign policy a centrepiece of their campaigns, and polling has shown international affairs are relatively low on voters’ list of concerns compared to the economy and immigration.

Yet the next U.S. president will have to respond to a growing number of crises abroad that have a direct American interest: ongoing wars in Ukraine and the Middle East, foreign interference threats posed by Russia, China, Iran, India and other countries, brewing unrest in the Indo-Pacific and climate change among them.

There are open questions, too, about how Harris and Trump will approach longstanding alliances like NATO and NORAD, and whether Canada will be put on notice to step up even more on defence after facing pressure on spending during the Biden and past Trump administration.

Here’s what Harris and Trump have each proposed or said about their foreign policy stances, and how Canada may fit in — or find itself out in the cold.

In explaining her foreign policy views, Harris has pointed to her record as vice-president in advancing U.S. President Joe Biden’s reliance on allies and global alliances.

She says her meetings and discussions with world leaders have prepared her for the presidency and shown those leaders she is ready to preserve U.S. leadership on the world stage.

“Vice-President Harris will make sure that America, not China, wins the competition for the 21st century and that we strengthen, not abdicate, our global leadership,” her campaign policy outline says.

On Ukraine, Harris has said the U.S. will continue to support its fight against Russia’s invasion and help Ukraine win on the battlefield, which she says will secure an end to the war. She has reaffirmed support for NATO to defend members from Russian aggression.

Harris has called Iran America’s “greatest adversary” in the wake of its direct attacks on Israel and pledged to ensure the Iranian nuclear program can never produce a weapon.

She has reaffirmed the U.S.’s commitment to Israel’s self-defence and, while using more forceful language in calling for an end to Israel’s military offensive in Gaza, has angered progressive and Arab American voters by not pushing for an Israeli arms embargo.

Recent statements on the Middle East conflict from the White House attributed to both Biden and Harris have not mentioned a ceasefire, although the Harris campaign says she is helping to secure one.

Her campaign says Harris is “committed to continuing and building upon the United States’ international climate leadership.”

Trump and Republicans have frequently referred to a Trump administration’s approach to foreign policy as “peace through strength.”

His platform calls for major military investments and modernizations, including an Iron Dome missile defence system similar to the one used by Israel, and higher pay for troops.

“Republicans will promote a Foreign Policy centered on the most essential American Interests, starting with protecting the American Homeland, our People, our Borders, our Great American Flag, and our Rights under God,” the 16-page party platform reads.

The platform mentions “countering China” and supporting the security and independence of nations in the Indo-Pacific, but mostly focuses on stopping Chinese economic advancement.

Trump has said he will secure peaceful resolutions to the Ukraine and Middle East wars within days of taking office. Yet he has not said if he wants Ukraine to win against Russia and has hinted at being open to Ukraine giving up contested land as part of negotiations. His platform does not mention Ukraine at all.

He has said Israel should end its campaign in Gaza “fast” but that it should destroy Iran’s nuclear facilities in response to Iran’s recent attacks. Iran, along with China, has been a frequent target of Trump.

Trump’s platform says he will “strengthen alliances” by ensuring they “meet their obligations to invest in our Common Defense.”

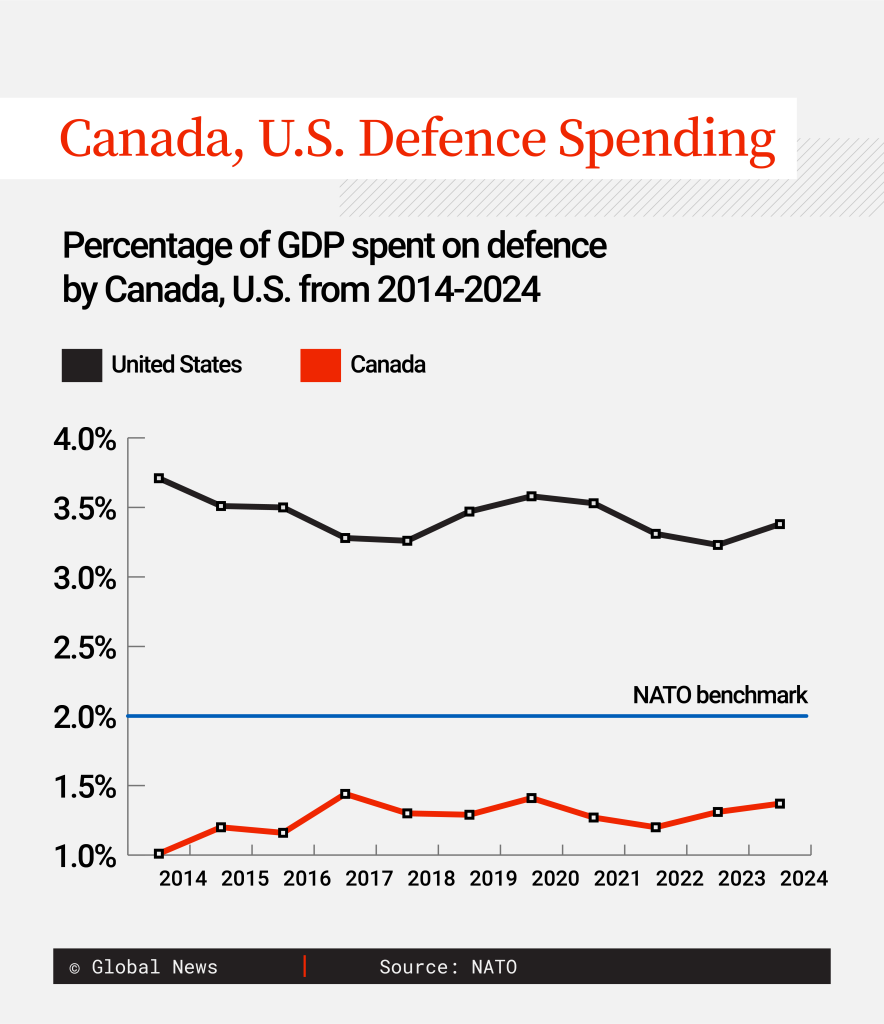

In public, he has spoken more plainly, saying repeatedly that he may not come to the aid of NATO allies that don’t spend at least two per cent of GDP on defence — even suggesting countries like Russia could “do whatever the hell they want.”

During his first term, Trump frequently complemented and said he “got along well” with authoritarian leaders whose governments are viewed as antagonists to the U.S., including Russian President Vladimir Putin, Chinese President Xi Jinping and North Korean leader Kim Jong Un.

Trump’s immigration policy is also closely connected to his foreign policy, arguing defence of America begins at securing its borders.

Although Canada will likely be able to find common ground with both a Harris or Trump administration on foreign policy, analysts say that won’t matter for as long as Canada continues to not meet its NATO commitments.

Canada is one of only eight countries in the 31-member NATO alliance not meeting the two-per cent defence spending threshold.

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau has said Canada is expected to meet the target by 2032.

However, the parliamentary budget officer said in a report this week that the current forecast is based on “erroneous” economic projections, and that no clear plan has been presented on how the two per cent target will be reached.

Whether U.S. and allied pressure on Canada to step up remains relatively civil or more assertive likely depends on who’s elected in November.

“Kamala Harris believes in compromising with allies, and Donald Trump would rather dictate to them and wants to see the colour of their money,” said Colin Robertson, a senior fellow at the Canadian Global Affairs Institute, who said Trudeau’s 2032 timeline likely isn’t sufficient for either candidate.

Even if Harris is elected and strikes a friendlier tone with Canada on defence spending, Republicans in Congress are expected to keep the pressure up.

One top Republican lawmaker, U.S. Rep. Mike Turner, recently wrote an op-ed that cast Trudeau, rather than Trump, as the true “threat” to NATO’s stability due to missed spending targets and deficient equipment that he said cannot be relied upon.

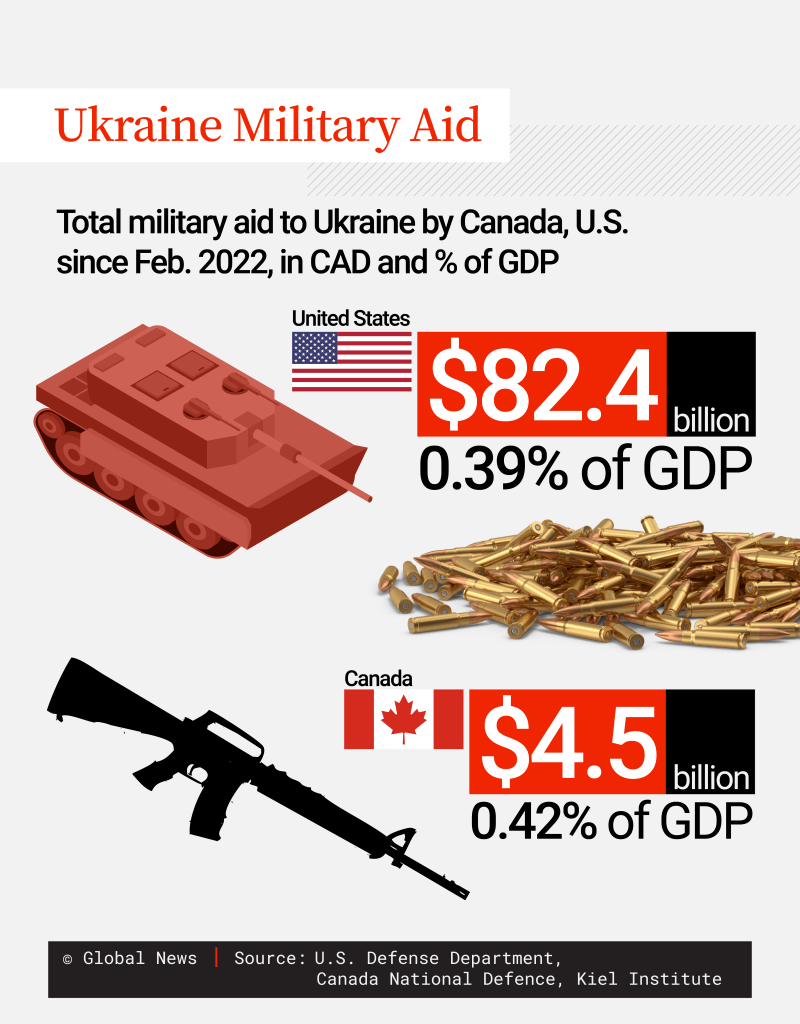

While Canada’s military aid contributions to Ukraine have been slightly higher than the U.S. in terms of share of GDP, Turner noted the Canadian aid pales in comparison in terms of actual equipment sent.

The larger issue, experts say, is that Canada’s defence shortfalls have created a “reliability and reputational deficit” that will continue to undermine its alliances on the world stage.

Recent immigration issues, like the arrests of multiple alleged terrorist attack plotters this year, may further isolate Canada, said Christian Leuprecht, a professor at Queens University and the Royal Military College and a senior fellow at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute.

If Trump were to pull back the U.S. from leading on issues like Ukraine aid and climate change, for instance — or even withdraws from NATO or NORAD, as some fear he will do — Canada may find a hard time exerting itself as a reliable partner.

Canada has also done itself no favours by denying requests from Germany and Japan — both key allies and trading partners — to export more natural gas amid energy shortfalls created by Russia’s war in Ukraine, Leuprecht said.

“We’ve made ourselves strategically less relevant to the partners we desperately need in the event of a Trump election to counterbalance unilateralism under Trump,” he said.

“There’s a risk of being left out in the cold, (and) this tendency of underinvesting in defence, in foreign policy … may come back to haunt us.”

A Harris administration may still present those same risks to Canada and exert a similar unilateral pressure — but with a “smile,” Leuprecht added.

The federal government has been proactively shoring up relationships with lawmakers and U.S. businesses to prepare for both a Harris and Trump administration.

Robertson said Canada will need to ensure it has a voice with either administration to address the economic and security threat posted by China in the Indo-Pacific.

© 2024 Global News, a division of Corus Entertainment Inc.

Ad Choices

Ad Choices